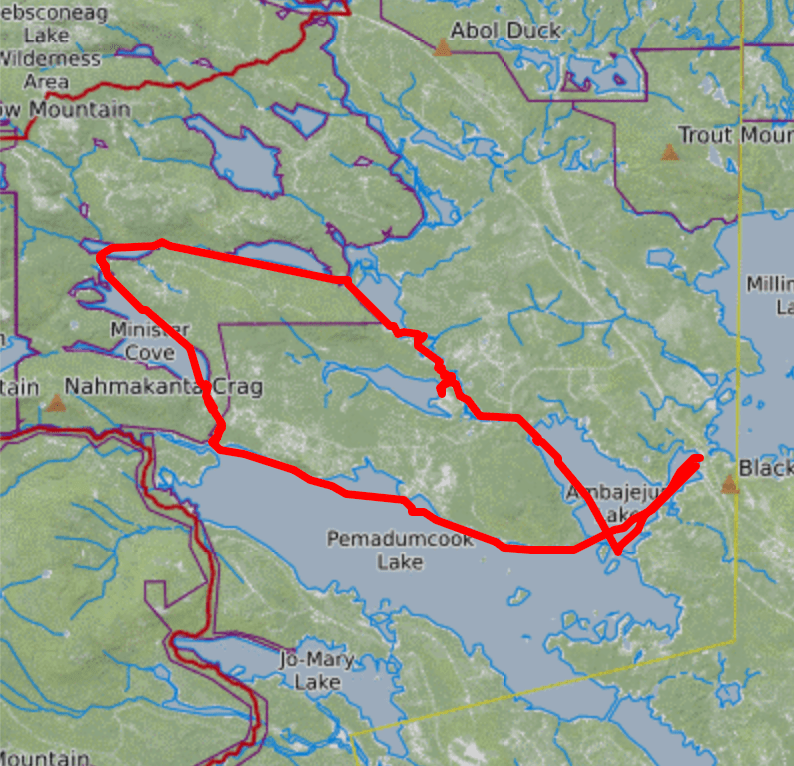

The Abenaki word Debsconeag, meaning “carrying place,” aptly describes the Debsconeag Lakes Wilderness Area, located southwest of Baxter State Park. Managed by The Nature Conservancy, this pristine parcel of land is home to remote ponds linked by a network of portage trails winding through mature forest. After years of dreaming about paddling here—inspired by the description in Quiet Water Maine by Alex Wilson and John Hayes—I finally committed to making it happen this summer. I invested in a solo canoe and gathered three friends with lightweight boats to join me, and together we planned a two-night, late-September adventure, navigating the area in a clockwise loop.

Like many great trips, it began with a night in our cars. We had reserved a campsite at Big Moose Inn and Campground across the street from the public boat launch at Spencer Cove, the starting and ending point of our adventure. Without tents to pack up, we ate breakfast, loaded the canoes, and were on the water shortly after sunrise.

Our journey began with a paddle across Ambajejus Lake, part of the Pemadumcook Chain of Lakes, which are actually sections of the West Branch of the Penobscot River. The river enters Ambajejus at its northwest corner, the route we would take on our return. For now, we paddled straight across the southeast end into Pemadumcook, a vast lake offering stunning views of Katahdin. Initially, we made slow progress, distracted by photo opportunities, but as the wind picked up, we shifted into serious paddling mode. Pemadumcook is known for its large waves, even on seemingly calm days, and we soon found ourselves battling swells and whitecaps. After some nerve-wracking moments, we decided to seek shelter on land. Angling to shore was challenging, though, and by the time we landed, our confidence was wavering. Just a few hours into our trip, we felt our chances of success slipping. But we knew conditions could change. We regrouped, snacked, hydrated, and marveled at the whitecaps until they gradually subsided. After about thirty minutes, we pushed off again, ready to face whatever challenges lie ahead and prepared to be flexible with our plan.

The wind allowed us to continue, and we reached our first portage of the day, at Whitehouse Landing, a wilderness camp with cabins and a bunkhouse, at 1 pm. Now, things were about to get interesting. None of us had ever portaged long distances before, and while we believed we could do it, we had no idea how tough it might be or how long it would take us. A few fishermen were relaxing around the fire pit, and I admit, if any had offered help, I would have gladly accepted. There’s no pride in portaging. But none did, so after refueling with food and water, we lifted our canoes on our shoulders and began walking. It’s the type of task you don’t overthink; you just start doing it.

My canoe is a 12-foot, 42-pound Esquif Adirondack. Earlier in the season, I had successfully portaged it over a quarter-mile of rough terrain, but I was anxious about the longer trails on this trip (the first portage is approximately two miles long). In preparation, I practiced carrying it through the woods around my house, and when I got tired, I decided to try dragging it. I’ve hauled a fully laden pulk sled long distances in the winter many times. Granted, snow offers less friction than grass, dirt, rocks, and roots, but I figured I could do it, and I discovered I could. So, after seeing the relatively smooth condition of the first portage, after a few hundred yards I decided to drag it. This process was sometimes very easy and other times much less so, but it did allow us to load our paddles, life jackets, and water bottles in my boat. With my friends’ lighter Kevlar canoes, we managed each portage in just two trips.

Of course, this process took time. We alternated between carrying and dragging the boats as far as we could, then returned for gear, repeating the process until everything was at the next body of water.

When we reached Third Debsconeag Lake, the waves once again gave us pause. The largest of the three Debsconeag lakes stretched ahead, followed by another portage to our campsite. It was after 4 pm, and the day was slipping away. Again, we began to reevaluate our plan. If we couldn’t reach our first campsite, we may need to turn around and retrace our route the next day. We decided to wait until 4:30 to see if the waves would calm. Thankfully, they did. Soon, we were paddling with renewed purpose, captivated by the beauty and remoteness of this wild place. Large boulders and an old-growth forest lined the lake, and the slanted sun illuminated the north shore in a mesmerizing evergreen glow.

The portage at the end of the lake was easy to find, marked by a bright yellow sign. One of my main worries going into this trip was locating the portage trails, but so far, they had been impossible to miss. By 6 pm, we began down the footpath through a moss-carpeted forest, home to moose, fisher, bobcat, pine marten, and surely, if they live anywhere, sprites and leprechauns. This was a tough stretch, and my friends took turns helping me carry my boat over the roughest sections. By the time we reached the campsite, we were working by the glow of our headlamps, but we had made it. It had been a twelve-hour day, but our efforts delivered us exactly where we wanted to be.

Loons kept us company the next morning as we wove around a picturesque island and the many large granite boulders populating Second Debsconeag, the smallest of the three lakes. At the easternmost end, we easily located our well-marked portage, which had been touted as the most challenging carry of our trip. True to its reputation, it required considerable effort to reach the next lake. Similar to the path between Third and Second, it was rocky and root-laden, which made canoe carrying and dragging tricky. Once again, though, the enchanting forest was a captivating distraction, even under our heavy loads.

When we reached First Debsconeag, we took a well-deserved long lunch break and pored over the beautiful map that Martha had crafted for us. We marveled at our progress so far while considering the obstacles that might await before pushing off again.

First Debsconeag is breathtaking. Katahdin was shrouded in clouds, but the base was visible, so we could all imagine the mountain there behind the mist. The lake’s still water mirrored the cloud patterns and tree line. We paddled in awestruck silence. High on the northwestern shore, we spied the boulder that marks the path to the ice caves, but we decided to forgo additional sightseeing in hopes of making it to our campsite before dark.

At the end of the First Debsconeag, we passed three remarkable beach campsites as we entered the Debsconeag Deadwater. This scenic stretch led us to the Penobscot’s West Branch, where we eventually encountered our first rapids. They were split by an island, and we chose the river right side, as it seemed to be a short, straightforward section. Two of us ran this, and we lined the third boat. Further down the river, we encountered the Passamagamet Falls, clearly unrunable on either side. What wasn’t clear, though, was the location of the portage. After scouting and consulting our notes, we discovered it was on the island that split the falls. Extracting our boats and gear from the island’s rocky shore was quite a challenge, but once done, the portage itself was short and easy.

Only one more obstacle remained – a series of rapids on the left that none of us wanted to run and a narrow, shallow, boulder-strewn channel to the right. We opted for the shallow channel and went through one by one, sometimes hopping out of our boats to maneuver around rocks. It was now 5 pm, but we knew our campsite was just around the bend—though we had no idea how beautiful it would be.

Rounding the corner into Passamagamet Lake, a stretch of white sand beaches soon came into view. I wondered aloud if it might be a campsite, and as we drew closer, we spotted a fire pit and a yellow sign confirming it was a fire permit-only site—a permit we had. After all our hard work, this spot felt like the perfect reward. We spent the evening swimming in the shallow water, carefully avoiding the freshwater mussels dotting the sandy bottom. As the sun dipped toward the horizon, it lit the fall foliage ablaze in a warm golden glow. To the north, clouds swirled around Katahdin, intermittently revealing glimpses of her upper flanks. We gathered around the fire late into the evening, watching the stars emerge in the clearing dark sky. It was a magical night—one that will remain with me for years to come.

The next morning, we left Passamagamet Lake, rejoined the West Branch, and paddled to the Ambajejus Boomhouse hoping for a glimpse into the region’s logging history, but it was closed—another reason to return. Ambajejus Lake was as smooth as glass, and by noon we had easily paddled its length, landing back at the cove.

Like all epic adventures, this one expanded my world. It was a powerful reminder of what a group of capable friends can accomplish together. We took on a tough challenge—and succeeded. I wonder what else we can do.

What an astounding and wonderful adventure! I must make this trip.

LikeLike

Love it and been in the area many times. My favorite of any area is Baxter State Park. Most recently at Kathdin Stream. Having slept in tents for many years I have decided never again. I’ve paid my dues. looking at trip to Baxter next August for hopelly 5 to 7 days. Hoping to hike to Chimney Pond and a very long shot of climbing Kathdin one last time. Was a breeze when much younger and in very good shape. See what happens.

LikeLike